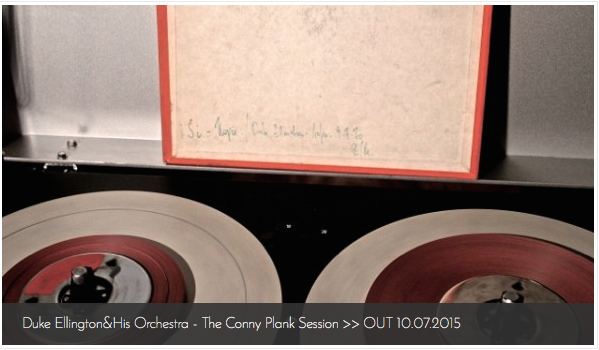

Latest update from the Grönland Records site, re: The Conny Plank Sessions issue on CD and vinyl, 10 July...

Duke Ellington’s musical works are seemingly well documented; the likelihood of finding a good, unreleased Duke Ellington recording is slight at best.

When Grönland Records called and told me they had found exactly that in Conny Plank’s estate and asked me if I wanted to give it a listen, I felt pretty honored, and excited. The music of Duke Ellington is – in my worldview – to jazz what Bach’s oeuvre is to classical music: THE great benchmark, or – to raise it up onto an even higher pedestal – the Old Testament, the alpha and omega. With both Bach and Ellington, you can sit down at a piano simply to go through it building chords and something great always happens. This music is so rich, and it is virtually indestructible.

I listened to the recordings for the first time in Grönland Records’ offices. One session, two songs: three takes each of “Alerado” and “Afrique.”

They weren’t just alternate takes, like you often get on reissues of jazz classics; you can really hear Ellington working. He’s not just looking for the best take to get something clearly defined, he’s experimenting.

The tempi change, solo instruments are switched around, and, on the last take of “Afrique,” you can even hear soprano vocals.

“Alerado” is a straightforward swing number, it features Wild Bill Davis on the organ, and, most notably, Cat Anderson on the trumpet, who provide a foundation for striking concepts of sonority and solo performance. The musical approach to “Afrique” is freer and more avant-garde; the foundation of the piece is a tom-tom based beat that is sustained throughout and layered with improvisations and arranged segments.

In addition to the musical aspects, this recording also documents a special moment: an American jazz legend in the twilight of his life encounters a young sound engineer and producer who is preparing to give pop a new sound – now that’s exciting, isn’t it?

I knew who Ellington was, but – as I must shamefully admit – I didn’t know anything about Conny Plank. To be more precise, I knew Conny’s work, but I didn’t know it had anything to do with him: Kraftwerk, Eurythmics, Ultravox, D.A.F. Although I grew up with 1980s synthpop… but I wasn’t aware of how important Conny was to that whole scene. The concept of the producer as a first-rate star wasn’t really a viable possibility until Rick Rubin showed up. Although Conny carried the weight to stand front and center, it seems highly improbable – based on everything I now know about him – that he ever would’ve wanted that. He exemplified the Prussian maxim mehr Sein als Schein [“be it, don’t flaunt it”].

That encounter is also the heart of an important Plank family narrative. The German Wikipedia entry on Conny Plank claims that Wolfgang Hirschmann passed on responsibility for the recording to Conny. Wolfgang Hirschmann was a sound engineer and longtime head of the WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk) big band. I talked to Mr. Hirschmann on the phone. He told me he knew nothing of these recordings and that he thought Conny was already in Hamburg at that time. There was even brief speculation that Justus Liebich may have done the recordings (he worked in Rhenus Studio at the time).

Mr. Liebich was kind enough to examine the master – the recording is Conny’s.

So that is certain. There is certainty about the location: Rhenus Studio in Cologne. The date is unclear.

Wikipedia mentions April 27, 1970, the date on the tapes themselves and the Ellingtonia list July 9, 1970 as the date Ellingtonia. The circumstances are also unclear: who, for example, is the female vocalist singing on the third take of “Afrique”? Stephan Plank even surmised that it was his mother, Mr. Hirschmann speculated that it may have been a Scandinavian lover of Ellington’s… The myths and legends abound.

Stephan Plank recalls his mother telling the story of that recording session as follows: Duke Ellington was looking for a place to rehearse in Cologne, Conny asked the owner of Rhenus Studio if he would let him use the premises, and politely asked Duke if he would allow him to do a no-frills recording of the rehearsals with matched stereo mics. This version of the story appeared plausible after the first digitization of the original tape. It lacked high tones, so it sounded “rehearsal roomy” – however, Ingo Krauss suspected that this sound had nothing to do with the recording, but with a poorly adjusted tape recorder. Ingo worked as head sound engineer in Conny Plank’s studio in Wolperath after his death, and his hunch was correct. He digitized the recording again himself, and his version is considerably more vibrant.

Further research revealed that two takes had already been released on CD. Both of those releases were more severely mastered; Ingo’s version, on the other hand, is left in a natural state.

Ingo Krauss heard the story of the recording from Christa Plank’s perspective as well. Her version is as follows: Ellington had himself paid to rent out Rhenus Studio for a “stockpile” session, i.e. to make recordings meant for use at a later, yet to be determined, date – and he hired Conny as his sound man.

However, the crux of this story is the same in both cases. Duke listened to the takes and praised Conny’s work. Conny admired Ellington and received recognition from the right person at the right time. Influence and recognition – it was a stroke of luck.

That was tantamount to being knighted and would be enough for a nice story in itself, but Ingo’s version contains an additional tidbit.

Conny was fascinated by how great the difference in tone was between his prior studio work and those takes; the Ellington big band was delivering something totally different, something better than he was accustomed to. It resulted in a recording that even Conny could be happy with. This session seems to have given an important impulse to his work, independent of the praise he received from the master.

This casts the bon mot often attributed to Conny that “every band gets the sound it deserves” in a different light; it no longer comes across as an arrogant remark, but as a clear conception of a simple fact: one can only produce what’s there – if the performance isn’t any good, technology won’t help either. So, for him, it was a moment of realization and revelation.

And ensuring that the performance was spot-on was one of Conny’s great talents. Independently of one another, artists he later produced repeatedly described how

vital his kindheartedness, tranquility and circumspection were to producing successful recordings.

And he was prepared to work for that. The Scorpions, whose first album was produced by Conny, relate how he even got in front of the band and danced!

On the topic of dancing… Duke Ellington had a habit of ending his concerts with a short lesson about how to snap one’s fingers if you wanted to be “cool.” (Duke Ellington Copenhagen 1969)

Making the claim that the encounter between Ellington and Plank was what later made Kraftwerk possible would be totally overstated, but the notion that, in that moment, something of the “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)” spirit was conveyed to Conny, and that it helped free him and loosen him up enough to stand undaunted in front of a band and dance is just too wonderful and lends these recordings even more radiance. I wonder if this story will soon be further embellished to mystical proportions…