An extract from the epic Ken Burns documentary Jazz pertaining to Duke Ellington's European tour in Spring 1939 has recently been uploaded to Youtube. Here it is...

On the subject of the European tour, there is a very interesting article I have been meaning to post here for sometime so the publishing of the above clip seems the perfect time to do so. The opinions expressed below about a concert given by the Ellington aggregation in Holland are jaw-dropping in their indifference. Bliss, I should have thought in contrast, would it have been in that dawn to be alive!

Here is the article with the link to the original source below.

DUKE ELLINGTON IN HOLLAND - 1939

By Mark Berresford, based on research by Joop Gussenhoven

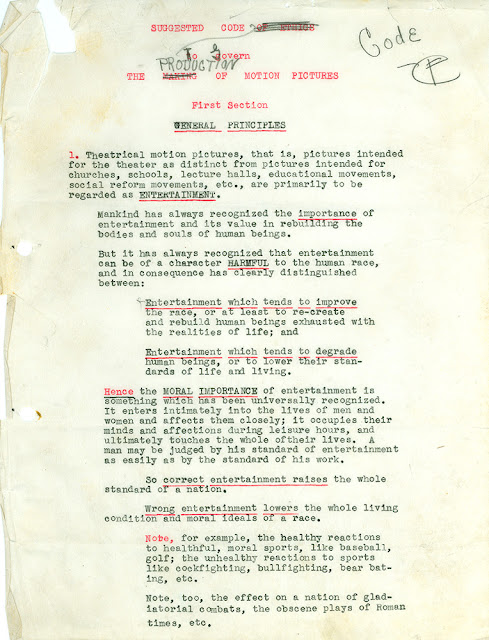

Picture: Duke, Iriving Mills and the band on the platform at The Hague railway Station, April 10th 1939

The 1933 European tour by Duke Ellington and His Orchestra has been extensively documented over the years, as like Louis' tour of the same year, it was Europe's first opportunity to hear in the flesh one of the most influential musicians in jazz. Less well-documented is the Duke's European tour in the spring of 1939; that it happened at all in the light of the crisis in Europe at the time, with war clouds already gathering, is all the more remarkable. Through the research of Joop Gussenhoven and Ate van Delden, it is possible to piece together the band's itinerary, and also present an eye-witness account of their concert in the Hague. J.P. van Blarkom, who was the former president of the Dutch Jazz Liga attended the concert and wrote an extensive report, which we present here for the first time in 61 years.

The Duke Ellington Orchestra, minus arranger Billy Strayhorn sailed from New York on Thursday 22nd March 1939, landing at Le Havre, France. On the 1st April Duke held a press conference in Paris and the next day he and the band travelled to Brussels and presented two concerts at the Palais des Beaux Arts. Returning to Paris on the 3rd April, they appeared later that day at a concert in the Theatre Nationale and repeated the performance on the following day. The band returned to Belgium to give two concerts in Antwerp on the 6th April, then on the 7th the band minus Duke travelled by train to Den Haag (The Hague), Ellington himself motoring there with Lennard Reuterskiold, who was managing the band's European tour.

There followed a hectic itinerary of three concerts in two days; the first on the evening of the 8th April in Den Haag. The next day the band travelled to Utrecht and gave a concert in the afternoon and later that day travelled to Amsterdam, where they gave a further concert. On the morning of the 10th April, a group of weary musicians, along with manager Irving Mills and their entourage made their way to Den Haag station to catch a train to Stockholm and to continue their lightning European tour. Fortunately for posterity an Ellington fan had taken his camera to the station to see the band off and the resulting photograph is reproduced herewith.

J.P. van Blarkom's account of the Den Haag concert makes interesting reading - although only 6 years had passed since the Duke's first European tour, the changes in the style and makeup of the band took van Blarkom and other members of the audience by surprise. The writer laments the passing of 'the old Duke' in forthright terms, even though the repertoire consisted of earlier Ellington standards. I have taken some liberties with the translation of van Blarkom's review to improve its flow and render it into better English, but the spirit of the original piece has been retained.

The Duke Ellington Concert, The Hague, 8th April 1939

After a seven year wait, we once again have had an appearance by the famous Duke Ellington band. The concert was practically sold out in advance, and while the name of Ellington practically rules the world of jazz, whether he still deserves this fame is open to question. It was a great performance, but thinking it over later that night at home, I wonder if 'Mike' (Spike Hughes' nom-de-plume in the Melody Maker) was telling the truth some years ago about Ellington losing direction.

Ellington had changed the stage layout of the band form his previous visit. Seven years ago the Duke sat centre stage; to his left sat the brass section, to his right the saxes and the rhythm section behind the Duke. This time the full band was seated in the middle of the stage, the Duke sitting to the left of the band and to his left Sonny Greer was seated with all his kettles and drums. Greer's drumming now sounded much too loud, sometimes even overdrumming instrumental solos. The bass stood between the saxes, who occupied the foreground, and the brass ranged in a row at the back. Fred Guy was seated at the extreme right.

The personnel of the band was the same as seven years ago except for two new trumpeters, the famous Rex Stewart and a certain Mr. Wallace Jones, who we hardly heard during the the whole show. In place of Wellman Braud we had Billy Taylor, but due to his placement in the band it was rather difficult to get an idea of his playing.

The band opened with East St. Louis Toodle-Oo, after which the Duke made his entrance to a tremendous ovation. After a short speech about being happy to be playing again in Holland, he announced the first number, Stompy Jones, which was played just as on the record. After that we got I Let A Song Go Out Of My Heart, featuring a beautiful duet between Hodges and Carney. The next number was Caravan, a tune I personally never liked, that is until this evening. Juan Tizol took two choruses and as far as I remember this was the first time we heard Tizol on valve trombone. He had a beautiful tone which surprised and delighted the whole audience. Mood Indigo came next, starting with the trio, as on the record, but with Jones taking the place of Whetsol. After the first chorus the Duke took a long solo and then a rescoring featuring the whole band,which really spoiled the wonderful melody. Merry-go-round, played as the Columbia record was the next number, and was probably the best number of the whole evening. The brass chorus was superb!

We were then treated to a new number The Lady in Doubt, in which Hodges got his first opportunity to shine, after which we got a totally new arrangement of Rockin' In Rhythm, into which was introduced Dallas Doings, featuring Rex Stewart. Barney Bigard took his bow with Clarinet Lament - what a tone! And what ideas - marvellous! Bigard was undoubtedly the star of the evening. Next it was Rex' turn to shine with Trumpet in Spades, which he played brilliantly and at a tempo which had to be heard to be believed. Sophisticated Lady was given as on the record, with a beautiful chorus by Lawrence Brown, but without Hardwicke - his wonderful solo on the record was now rewritten for the four saxes. Incidentally, we heard practically nothing of Hardwicke all evening.

Show Boat Shuffle was played as the record and was followed by an old favourite of some years ago, Black and Tan Fantasy, but the old melodic power of this melancholy tune was lost in the new arrangement. It was now a concerto for Cootie, Tricky Sam and Bigard, who each got a chorus to shine, bound together by Duke's piano playing. However the whole concept of the tune was lost - what a pity. At this point there was an intermission which concluded the first part of the concert.

Summing up, there were indeed some great moments, but in the old days Ellington played jazz, real and pure jazz. Now he was playing show jazz, good show jazz at that, but something was missing. The Duke had become fat and Ivie Anderson had become old. Even the Duke himself must have realised this change, for as he explained in an interview "Jazz is music, Swing is business." He is touring with Irving Mills, who was at the concert, and I feel that with Mr. Mills business comes first, so the Duke couldn't play jazz. We will probably never know the real reason.

After the interval Ivie Anderson came on and sang Alexander's Ragtime Band, Solitude and It Don't Mean A Thing, the latter tune giving us something of the old Ivie. We were lucky to have another number by Ivie, I think The Scronch, but I'm not absolutely sure, as it was a new number and was unannounced. Cootie then got his chance in Echoes of Harlem, after which the Duke announced that the band would now give an impression of a jam session, with two small groups, one led by Bigard and the other by Hodges. It sounded nice, but we have always had other ideas about jam sessions. These two tunes were played by Bigard, Rex and Tizol with rhythm in one group and Hodges, Brown, Cootie, Carney and rhythm in the other.

Now we got a new composition by Juan Tizol. I don't know know its name, but it really was a big surprise to us all. The first two choruses were played by Tizol (really wonderful) and the Duke, but not on the piano as one would expect, but on a tom-tom. He played them with both hands and got a very astonishing Bolero-effect. Hodges played a nice soprano sax chorus and the tune ended as it started, with Tizol and the Duke. The evergreen Tiger Rag appeared to end the concert - we heard a great chorus from the three trombonists, plus Hodges, Brown, Bigard, Red, the Duke and Cootie. Then without a word, the Duke left the stage and the concert seemed to be over. However, after a few moments he returned and we got as an encore one of his latest compositions, Swamp Swing, which funnily enough was the best tune of the evening. The concert finished with St. Louis Blues, in which we heard Cootie, the three trombones again, Bigard (and how!), Hodges on soprano sax, Tricky Sam and a brass chorus, finishing with a quote from Rhapsody In Blue.

Overall it was a great concert, but we who belong to the old guard were rather disappointed. All the great old tunes were rescored, and in my opinion not too successfully. The old power of the band was lost and the Duke was really playing to the house. The soloists were all great, but the Duke, who in the early days wrote for the whole band as one man, now was writing for each member of the band individually. The younger generation were wild with excitement, but they had not heard the old Duke in 1933. The audience was still laughing at Tricky Sam's chorus on Black and Tan Fantasy, so after all these years they still haven't learned to feel the Ellington spirit.

SourceThe incident related in the Burns documentary I always thought would have been the basis of a great film à la Hitchcock's The Lady Vanishes. Mick Carlon got there first, however, telling the story of the ride through Nazi Germany in his book Riding on Duke's Train.