Duke Ellington on Stage and Screen

Duke Ellington on Stage and Screen

Leon Robbin Gallery

February 14, 2017

August 15, 2017

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899–1974) was one of the most prominent musical figures of the 20th century. His music was often defined as “jazz,” but he sought to create a body of music “beyond category.” In fact, he preferred to be called simply an “American” composer. The breadth of Ellington’s output was astounding. In addition to writing hundreds of jazz standards, including “Mood Indigo” and “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” he served as the leader of America’s most stellar big band for nearly a half century and composed numerous film scores, musicals and large-scale orchestrated works. Even more importantly, he was one of the most prominent public figures in American history.

Born and raised in Washington, DC, Ellington moved to New York in 1923, where he soon gained national prominence as the featured performer of Harlem’s famous Cotton Club. In 1920s New York, Ellington was drawn to the socially-conscious, artistic flowering commonly referred to as the Harlem Renaissance. He was especially drawn to the work of Langston Hughes, who in his 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” described jazz as “one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America: the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul – the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world.” Ellington took this statement to heart when, in the 1930s, he made his way to Hollywood. This exhibition focuses on some of Ellington’s earliest experiences as a composer for stage and screen, and his desire to serve as an artist promoting “the inherent expressions of Negro life in America.”

Original manuscripts, photographs and ephemera in this exhibition are selected from the Arthur Johnston Papers (GTM 091217); the Martin J. Quigley Papers (GTM GAMMS142); and The Leon Robbin Collection of Music Manuscripts and Letters of Composers in the Booth Family Center for Special Collections.

1

In 1945 Ellington copyrighted as “composer” his musical setting of the opening verse to “Heart of Harlem,” a poem by Langston Hughes. Ellington and Hughes first met during the height of the Harlem Renaissance – the mid-to-late 1920s – when the Duke Ellington Orchestra was in residence at the Cotton Club. Hughes was a great fan of Ellington’s music, and Ellington aspired to channel the racial uplift he found in Hughes’s writings. In 1936, the pair began work on a musical titled Cock o’ the World, but unfortunately, this project was never completed. “Heart of Harlem” was their only collaboration.

*This holograph of Ellington’s score was Hughes’s personal copy. The changes to the text, made sometime after the song’s publication, are in Hughes’s hand.

2

Duke Ellington and His Orchestra were featured in a variety of short films and feature-length motion pictures in the 1930s. Belle of the Nineties was one of the most successful films from this era. The film was based on a story written by Mae West titled “It Ain’t No Sin.” West also served as the film’s leading lady, and while negotiating with Paramount, she insisted that Duke Ellington and His Orchestra be hired to accompany her on several key musical numbers in the film. In Belle of the Nineties, West plays the role of Ruby Carter, the featured singer in a New Orleans venue called The Sensation Club. The Ellington Orchestra accompanies her during performances of several Arthur Johnston/Sam Coslow songs in the film – most notably “My Old Flame” and “Troubled Water.”

West was a loyal fan of Duke Ellington and his music, and it was thanks to her influence that he was contracted to perform in both Belle of the Nineties and Murder at the Vanities – two Paramount films shot simultaneously in Los Angeles during the summer of 1934.

*Promotional materials describing the musical numbers composed by Arthur Johnston and Sam Coslow for Belle of the Nineties.

*Publicity photo of Mae West. Never shy about her sensuality, West’s character in Belle of the Nineties claims: “It is better to be looked over than to be overlooked."

*Paramount Pictures publicity materials for Belle of the Nineties. West’s original title for the film, It Ain’t No Sin, was changed due to the censors’ demands for a less provocative title.

3

Murder at the Vanities is a musical murder mystery that takes place in a Broadway theater called the Vanities. Duke Ellington and His Orchestra were hired to perform a key scene in the film, originally titled “Ebony Rhapsody,” featuring music composed by Arthur Johnston with lyrics by Sam Coslow. When Ellington was contracted to appear in this film, director Mitchell Leisen assured him that he and his orchestra would be represented in an elegant and respectful manner.

*Typescript of the original script for “Ebony Rhapsody.”

*Letter to Arthur Johnston from E. Lloyd Sheldon, producer of Murder at the Vanities, dated May 4, 1934. The film underwent extensive editing before its release, which required last-minute music additions supplied by Johnston and Coslow.

4

The Ellington scene in Murder at the Vanities begins with Franz Liszt performing his Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 alone at a piano. The stage resets to a performance of the same work by an all-white symphony orchestra. As the orchestra plays, Ellington and his musicians deftly insert themselves within the ensemble, adding jazz licks between phrases until the white conductor and his musicians depart in frustration. Liszt’s music is then transformed into the “Ebony Rhapsody,” which brings great pleasure to the young women, black and white, who appear on stage and dance with great abandon. Ellington is presented as the triumphant composer/ performer of the modern era. The scene ends abruptly when the original white conductor returns with a prop machine gun and mows down everyone on stage with a barrage of bullets.

*Murder at the Vanities poster (1934)

*Promotional photo for Murder at the Vanities featuring composer Arthur Johnston and the chorus girls from “Ebony Rhapsody.”

*Two image stills from the “Ebony Rhapsody” scene: the first showing Duke Ellington as the triumphant composer/performer, the second showing the frustrated conductor Homer Boothby (played by Charles Middleton).

5

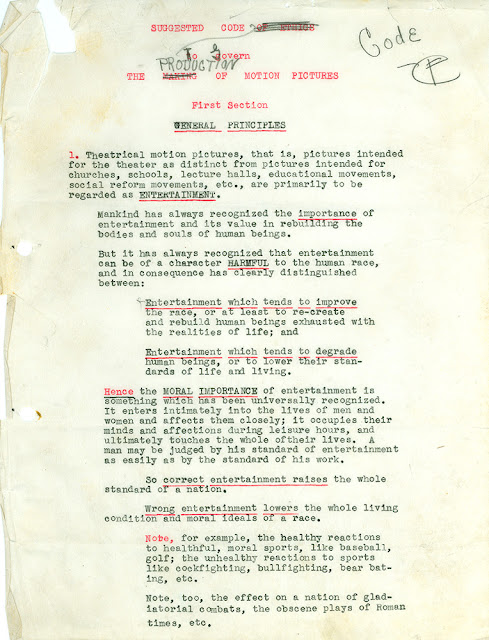

Murder at The Vanities was the last film to be released before the Motion Picture Production Code went into effect in 1934. This Code was originally created by Martin J. Quigley (editor of Motion Picture Herald) and Father Daniel A. Lord, a Jesuit priest. The primary purpose of the Code was to create a set of moral guidelines for the film industry that prevented a movie from “lowering the moral standards of those who see it.” In an effort to break the Production Code’s rule against showing “Rape,” the film’s director and producer retitled Duke Ellington’s scene “The Rape of the Rhapsody.” In the final version of the film, viewers see a “program” for this scene before the action takes place. This program describes the symphony orchestra’s performance as “The Rhapsody,” the Duke Ellington Orchestra’s performance as “The Rape” and the conductor’s return with a machine gun as “The Revenge.” In short, “Ebony Rhapsody” was transformed into a metaphorical lynching.

*Three pages from the original Motion Picture Production Code written by Martin Quigley and Daniel A. Lord, S.J.

*Image still from Murder at the Vanities showing the “program” for Duke Ellington’s scene.

6

Ellington was deeply angered by the way his scene in Murder at the Vanities was edited. And he demanded that Paramount Pictures make restitution (see the discussion of Symphony in Black below). But Ellington did not blame Arthur Johnston. Several weeks after the film’s release, Ellington sent Johnston a custom-made Christmas card that he had designed himself. As the royalties statement from 1935 reveals, Johnston continued to receive payments for his music, even after screenings of Murder at the Vanities ended.

*1935 Royalties Statement issued to Arthur Johnston.

*Christmas card from Duke Ellington to Arthur Johnston postmarked December 11, 1934.

7

Duke Ellington was very mindful of his public image, and after the debacle of Murder at the Vanities, he demanded that Paramount fund a short film that would effectively reinstate the image of Ellington as a socially-conscious American composer. The result was a nine-and-a-half minute musical shorttitled Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life. Filmed in December 1934/January 1935 at Paramount’s east coast studio on Long Island, NY, Symphony in Black presents four vignettes of contemporary life in the African American community: The Laborers (blue color workers), A Triangle (love and heartbreak), Hymn of Sorrows (religious practices and death) and Harlem Rhythm (nightclub entertainment). The entire film is pantomime, with music composed by Ellington supplying the emotional background to the imagery on screen. Among many highlights, the film features the screen debut of Billie Holiday, who sings a variation of “Saddest Tale” in the second part of the film.

Symphony in Black was released in September 1935, and shortly thereafter was awarded an Oscar for “Best Musical Short Subject.”

*Three image stills from Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life (1935).

8

After the success of Symphony in Black, Ellington composed numerous other large-scale works that engaged with the topic of African American history. Undoubtedly, his most famous work in this vein was Black, Brown and Beige, a multi-movement concert work that was premiered at Carnegie Hall in 1943. Less well known, but equally important, was Jump for Joy, an all-black musical revue that premiered on July 10, 1941 at the Mayan Theater in Los Angeles. The show ran for 122 sold-out performances over the course of three months. Ellington tried to bring it to Broadway, but its black pride message was considered too controversial for New York audiences. Ellington explained that his goal in composing the work was to “take Uncle Tom out of the theater and say things that would make the audience think.” By rejecting the negative stereotypes of African Americans so often portrayed in the media, Jump for Joychallenged the myth of black inferiority and offered instead an unabashed celebration of African American culture. Comprising approximately thirty songs and sketches (the script was edited continuously), Jump for Joy presented audiences with a work that instilled racial pride. As Ellington explained years later, Jump for Joy was his “contribution to the Civil Rights cause… It was the hippest thing we ever did.”

*Promotional poster for Jump for Joy.

*Duke Ellington’s original typescript outline for Jump for Joy.

9

*Interior pages for Duke Ellington’s typescript outline for Jump for Joy.

*Autograph manuscript of two pages from the working manuscript in piano score for Duke Ellington’s Jump for Joy (1941). The orchestration is suggested by the juxtaposition of the parts with the names of Ellington band members noted at the beginning of the first page.

*An excerpt from a later, more developed version of the score for Jump for Joy (1941). This section is from the end of the musical.

Acknowledgments:

Exhibition curated by:

Anna H. Celenza, Thomas E. Caesteker Professor of Music, Georgetown University

Gaelle Pierre-Louis (SFS'2017)

Gaelle Pierre-Louis (SFS'2017)

Sources:

Faith Berry, Langston Hughes: Before and Beyond Harlem (Westport, CT: Lawrence Hill, 1983).

Harvey Cohen, Duke Ellington’s America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010).

Edward Green, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Duke Ellington (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Theodore R. Hudson, “Duke Ellington’s Literary Sources,” American Music 9/1 (Spring 1991): 20-42.

Langston Hughes, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” The Nation (June 23, 1926).

Arnold Rampersad, The Life of Langston Hughes, Volume 1: 1902-1941: I, Too, Sing America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986).

Klaus Stratemann, Duke Ellington Day by Day and Film by Film (Copenhagen: JazzMedia ApS, 1992).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.