On the eve of the première performance of his new Ellington suite, Valedicition, Ethan Iverson published the following post on Substack...

TT 278: "In A Mellotone" and "Come Sunday"

More on the Ellingtonian theme

Tomorrow and Saturday, during Ellington: From Stride to Strings at the Grange Festival, I am accompanying Dominck Farinacci in “In a Mellotone” and Anush Hovhannisyan in “Come Sunday.”

1940! The first recording of “In a Mellotone” is a classic, pure joy and genius packed into three minutes from the famous Blanton-Webster band.

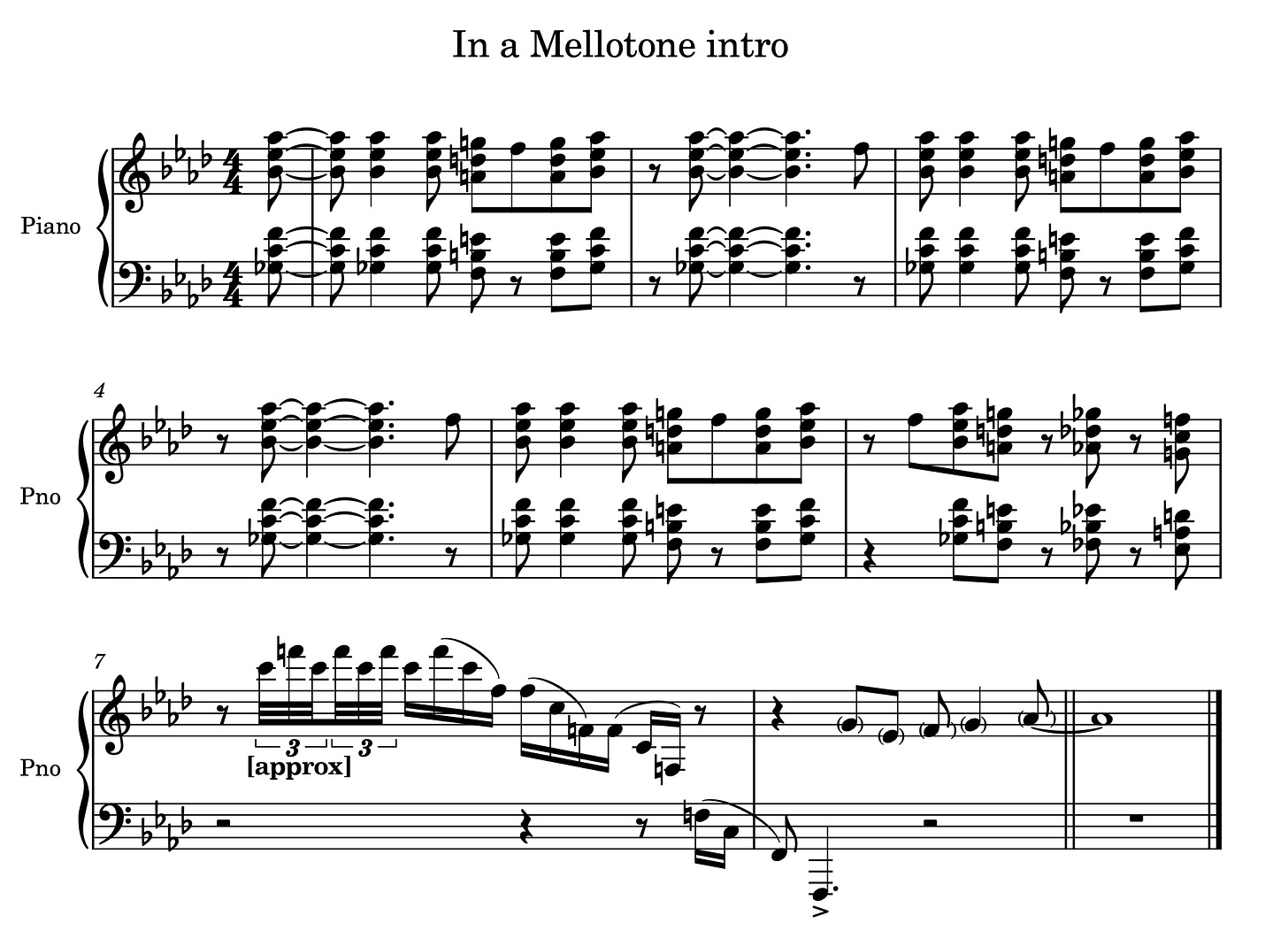

The piano intro seems notably important. I doubt Duke Ellington was exactly the first to utilize these stacks of fourth chords on parallel dominants, but this was surely one of the earliest occasions when they are used for this kind of percussive effect on record.

Literally everyone has played these voicings since, including Red Garland, Wynton Kelly, Cedar Walton, McCoy Tyner, and Herbie Hancock.

The piano intro to “In Mellotone” is almost as much part of the tune as the piano intro to “Take the A Train,” but I’ve never heard anyone emulate Jimmie Blanton’s interesting counterpoint underneath.

Cootie Williams and Johnny Hodges take great solos, but it is also noticeable how these cats haven’t heard bebop yet, for Hodges’s many double-time passages sound more like a European technical etude than Charlie Parker. (Later, a Ducal horn soloist like Paul Gonsalves would use bop phrasing in double-time passages.)

There’s also quite a lot of written double-time for the saxes. Indeed, from a purely technical perspective, “In a Mellotone” must be one of the hottest big band charts of the era.

”Come Sunday” was premiered as part of Black, Brown and Beige. The famous tune was given to Johnny Hodges. There is a recording of the suite at Carnegie Hall in 1943, there are also at least two wonderful studio sessions of “Come Sunday” featuring Hodges in the lead.

Comparing these historical recordings offers a somewhat obvious insight: there’s absolutely no improvisation or decoration. The harmony is immutable, the emotion is precise. Hodges phrases the melody the same every time. Any kind of tempo or forward motion is imperceptible as the hymn suspends over the bare minimum of support.

The later and more-familar studio recording has Mahalia Jackson (both with the band or almost a cappella) or Ray Nance on violin. Those are gorgeous performances as well, but the earlier starker setting for Hodges has now firmly caught my imagination.

As always, Duke Ellington is simply beyond category...

No comments:

Post a Comment