|

| 31 July 1955 |

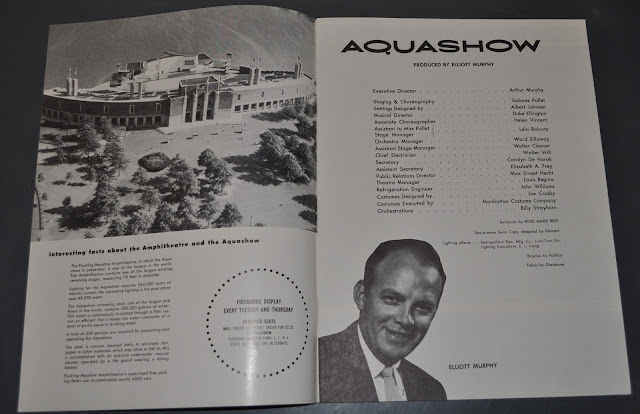

…the 1955 season brought in an entirely new challenge to the Parks Department vision. The star attraction was Duke Ellington, famed jazz composer, and his orchestra. Ellington’s presence immediately made Department of Parks officials nervous. Interdepartmental communications included inquiries as to whether Chief Designer, Stuart Constable, was “keeping a close eye” on that year’s program. He could not “let Murphy turn this into a loud, disorderly outdoor jam session" and warned that "he always needs watching.” In another Department memo, Constable reassured colleagues; “Murphy stated that the music will not be of the rock and roll type. We will however, watch this closely.”

Their concern stemmed from conceptions of Ellington and his chosen idiom — jazz — as well as its successor, rock ‘n’ roll. But here Parks officials' anxieties exposed the conflicting cultural currents at work in postwar America. By the 1950s, Ellington was highly regarded. He had spent two decades cultivating a professional persona as a highly skilled, “serious composer,” and many Americans would have perceived Ellington as conservative elder statesman of the genre. Characterized by historian Harvey G. Cohen as "Harlem's Aristocrat of Jazz,” Ellington’s image evaded racial stereotypes that excluded many African American performers from mass appeal. By the time of his gig with the Aquashow, Ellington had long since built a multi-racial audience and distanced himself somewhat from the Cotton Club and Harlem.

But white critics from the early to mid-20th century cast jazz as a racialized primitive genre, lacking melody or sophistication. Scholar, Maureen Anderson, affirms that until 1960 many writers continued to equate their distaste for jazz with a disdain for African Americans. In the case of the Parks Department’s unease, it’s possible they continued to associate Ellington with the racialized, improvisational music of the 1920s. Moreover, both jazz and rock ‘n’ roll appealed to younger generations. According to musicologist, James Wierzbicki, both genres prompted similar white assumptions of the music’s corruptive power “by conservative members of an older generation.” This may very well have applied to Robert Moses and his colleagues, whose approval of Ellington did not go beyond reasoning that he would be “OK,” and who, from the early days of Flushing Meadow’s postwar improvement, expressed a wariness of the growing black population in nearby Corona.

Ellington’s ties to jazz, however, were still racialized, coded as urban and understood by the Department of Parks as a potential threat coming to Queens. Particularly troubling to them seems to have been Ellington's (and jazz's) associations with musical improvisation, as evidenced by Moses' concerns about a possible "outdoor jam session." While the disorderly sounds of jazz could be contained within the walls of a Manhattan night club or by the conventions of "segregated" radio programming, the open-concept amphitheatre gave Ellington direct sonic access to hundreds of households in the vicinity of the park.

Despite these concerns, Ellington's performance received positive press from around the country. In African American newspapers he was lauded not only for the performance but for his role as musical director of the all-white Aquashow. For Elliot Murphy's part, he had in the end successfully recruited one of America's most respectable and refined artists for amphitheater performances. The enticement of Manhattan’s best acts to the amphitheatre, of course, had been one of the Parks Department's earliest aspirations for the venue. Their irritation with Ellington's tenure, however, suggests that only some parts of Manhattan were deemed suitable for export to the suburbs.