For the record, from 2018, Peter Gardner's piece for Dawkes Music.

…and finally ‘Lotus Blossom’

19th April 2018

I travelled with a young saxophonist who had never seen the great man before. The journey was uneventful and we arrived on time at Preston railway station. Then we made our way to Preston’s Guild Hall for the second concert of the evening. In a foyer we came across a large crowd of people facing closed doors that led into the auditorium. The doors were manned by a number of ushers and security staff. Word quickly spread that the start of the first of the evening’s concerts had been delayed and that the first concert would end in about thirty or forty minutes. As a result, the second house would be starting late. The ushers and security staff, more than willing to try to explain what had caused the delay, went through the foyer chatting to groups and answering our questions.

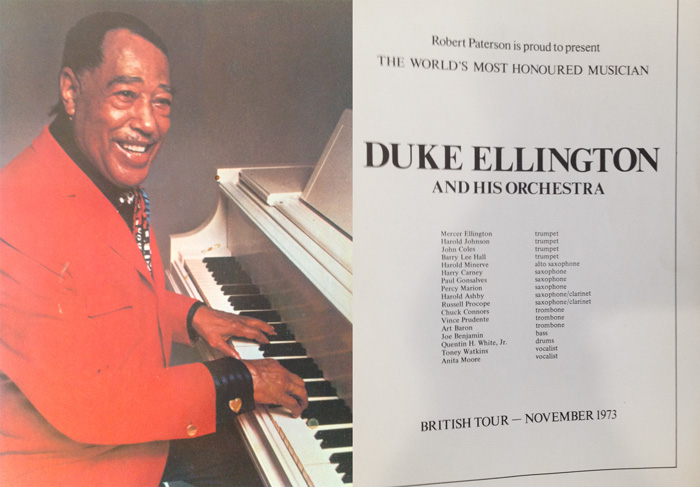

As part of his British tour in November 1973, Duke Ellington and His Orchestra had played in Dublin on Thursday 29th November and the next day had flown to Liverpool in plenty of time for their two evening concerts in Preston. Unfortunately, one of the ushers told us, the musicians and their instruments had somehow got separated. One of the rumours in the foyer was that at the time the musicians were flying eastwards, the plane carrying their instruments was on its way to America. Eventually the band and instruments were reunited at Preston’s Guild Hall, though by now they were unable to start the first concert on time. Rather than cancel a performance, Ellington decided to start the first concert late and play straight through, without an intermission. The second concert would then start late and again there would be no intermission. But, the ushers were keen to stress, Ellington would be playing two full concerts; nothing would be cut.

Ellington Programme – British Tour, 1973

Next day Preston’s local paper, The Lancashire Evening Post, told a different, but more complex story. The band, as arranged, had flown from Dublin to Liverpool, which I took to be Liverpool’s Speke Airport, later to be named the John Lennon Airport. However, “because of payload restrictions” the band’s instruments “had to go on a different plane” and this plane was going, not to Liverpool, but to Manchester, “where”, the Post informed us, “a truck was waiting to bring them (the instruments) to Preston. But this plane could not get into Manchester for fog and was diverted to land at Liverpool.” The truck that had been waiting at Manchester’s Ringway Airport then set off for Liverpool only to be “involved in an accident” which prevented it continuing with its journey.

Meanwhile back at the Guild Hall, “entertainments manager Vin Sumner and his staff managed to hire a van and, even harder in the early evening, to find a driver to speed to Liverpool and pick up the instruments. They finally reached Preston an hour after the first house was due to begin.” Nevertheless, despite the delay, “fans of both houses got their full quota of Ellington’s music.”

I had not been terribly optimistic about the concert for some time and the delayed starts on that Friday evening in Preston did nothing to change my mood. A little over a month earlier, on 24th October to be precise, Ellington and His Orchestra had performed the third of Ellington’s Sacred Concerts on behalf of the United Nations at Westminster Abbey. The reviews for that concert were not encouraging and seventy-four-year-old Ellington, it was suggested, was in poor health. Tenor saxophone star, Paul Gonsalves, had also been taken ill and although a photo of Gonsalves in full flow appeared in the programme that was produced for the British tour, he was no longer with the band. Saxophonist and flautist, Norris Turney, had also departed after a musical disagreement, and there were other omissions.

Over the years I had seen Ellington trumpet sections that featured ‘Cat’ Anderson, Clark Terry, ‘Cootie’ Williams and Ray Nance, but by 1973 all of these stars had gone or, at least, were not part of the Ellington band we were about to hear. There seemed to be a change of drummer as well. On the three previous occasions I had seen Ellington, Sam Woodyard had sat behind his two bass drums and booted the band along with a primitive urgency. Rufus ‘Speedy’ Jones had then appeared with the Duke on an Ellington tour that I missed, though ‘Speedy’ Jones was another who by now was a former sideman. The new drummer, and some reports said he was only twenty-one, was Quentin H. White, Jr., making him, by far, the youngest Ellingtonian I had ever seen. And while it was pleasing to read in the programme that Chuck Connors, who had been with the Duke since 1961, was one of the trombonists, those with some knowledge of great Ellington line-ups must have been saddened that Lawrence Brown was no longer in the trombone section or available for solos that evoked the Blanton-Webster days and beyond.

Duke Ellington (L) with Johnny Hodges (R)

But, given my preferences, the major absentees would be in the reed section. Gonsalves was no longer available to create either frenzied Newport moments or deliciously sinewy ballads. The pristine clarinet playing and the robust in-your-face tenor sound of Jimmy Hamilton wouldn’t be heard either. After more than twenty-five years with the Duke, Hamilton, according to some reports, had opted for the slower-paced life of the Virgin Islands. Yet, the major loss amongst the reeds was the irreplaceable Johnny Hodges, whose sublime tone and eloquent minimalism had made him the Duke’s supreme soloist for most of their careers. As Ellington said, “Never the world’s greatest showman or greatest stage personality, but a tone so beautiful it sometimes brought tears to the eyes – this was Johnny Hodges…Because of this great loss, our band will never sound the same again.” Hodges had died in May, 1970, aged sixty-two.

The first concert ended and a little later we took our seats. The orchestra entered from the back of the stage and veteran baritone saxophonist Harry Carney counted the band in. The piano stool remained empty. I recall the band playing ‘Perdido’ before the Duke’s entrance, though one account says it played both ‘C-Jam Blues’ and ‘Perdido’ before Ellington took to the stage. In those days audiences rarely stood to show their appreciation of their heroes and heroines, and the audience at the Guild Hall contented itself with applauding mightily as the Duke made his way through his musicians to the piano. Looking back, I’m certain we should have got to our feet.

Some of the highlights, as I remember them, were Russell Procope’s clarinet playing and Carney’s majestic baritone. Procope had what I always regarded as one of the great New Orleans sounds on clarinet; it was full, round, warm and woody, and his attack was a throwback to earlier Crescent City clarinet legends. A little research, however, shows that he hailed from New York. (A reminder that tones are personal, not geographical?) As for the band’s baritone player, Gerry Mulligan once observed that Duke Ellington has two sax sections and one of them is called ‘Harry Carney’. Now that the band was without Gonsalves, Hamilton and Hodges, their replacements being Harold Ashby, Percy Marion and Harold Minerve, Carney’s rich baritone seemed more prominent than ever. On bass Ellington had Joe Benjamin, a musician who had worked with just about everyone. I remember that he played superbly at the Guild Hall. Many years earlier Ellington used “Mr. J. B.” to refer to the astounding Jimmy Blanton. Apparently he was now reusing the title to refer to Joe Benjamin. Praise indeed.

Harry Carney (Bari Sax)

There was also a low point. Trumpeter Harold ‘Money’ Johnson gave us an Armstrong-like version of ‘Hello Dolly’, which wasn’t terribly good. It was part of the concert where a jocular Ellington predicted what music would be around in the coming centuries. I have never fathomed why the Duke himself or anyone who played with him needed to move outside the Ellington-Strayhorn songbook for inspirational material. And predicting what future generations would be listening to seemed an ideal opportunity to be optimistic and play something Ellingtonian.

The finale was wonderfully moving. All the musicians had played what appeared to be their final piece and left the stage and we applauded for an encore. After a while Ellington returned on his own. He played Billy Strayhorn’s ‘Lotus Blossom’. Strayhorn had worked with the Duke for over twenty-five years, and, as Robert Palmer has noted, he “was capable of interacting so seamlessly with Ellington that even the two of them had trouble pinpointing where one man’s contribution ended and the other’s began.” Strayhorn’s death in 1967 had affected Ellington deeply and the album ‘…and His Mother Called Him Bill’ (1), Ellington’s tribute to Strayhorn, was recorded just a few months after Strayhorn’s death. The album has many emotionally charged moments, but perhaps the most touching was when, with the noise of musicians chatting, packing their instruments and getting ready to leave the studio, Ellington played ‘Lotus Blossom’. That spontaneous studio performance has a few slips, but to close his November Guild Hall concert Ellington, alone at the piano, played it perfectly to an audience that I felt was well aware of its significance.

Ellington bowed graciously and left the stage. The delays with the instruments and two concerts without intermissions, would have made it a demanding day for a healthy man half his age. We applauded long and hard, but we knew in our hearts that no one would return to play. The tribute to Strayhorn was a fitting closure.

The next day the Ellington Orchestra continued its tour. As Patricia Willard would later write, “By December 1, when the band was to perform a pair of concerts at the Congress Theatre at Eastbourne on the south-east of England, it had performed in sixteen nations in five weeks.” In those five weeks the band had “only two ‘off’ days” and they “were spent travelling.” On 2nd and 3rd December the band had engagements in London and on Friday, 7th December, one week after appearing at Preston’s Guild Hall, Duke Ellington and His Orchestra gave a concert at the Academy of Music, Philadelphia. That was the Ellington way: day after day, week after week, year after year, and, in his case, decade after decade.

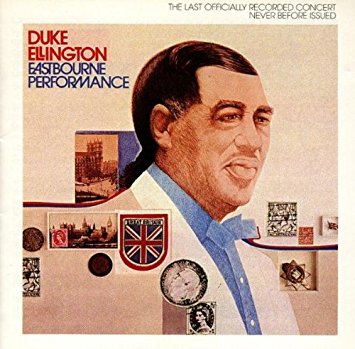

Eastbourne Performance LP

The concerts at Eastbourne’s Congress Theatre were recorded and eleven pieces from the concerts were later issued on an LP called ‘Eastbourne Performance’ (2). One of the most prominent soloists on these tracks is Ellington himself, who, despite everything, sounds on fine form. Other soloists on the Eastbourne album include tenor saxophonist, Harold Ashby, on ‘I Can’t Get Started’, trumpeter, Johnny Coles, on ‘How High the Moon’ and ‘Money’ Johnson on ‘Basin Street Blues’. At least altoist Harold Minerve found something suitable in the Ellington-Strayhorn songbook; he soloed on the Duke’s ‘Don’t You Know I Care?’.

Many years later I realised that life for Ellington during that British tour was even more fraught than I had imagined. On 25th November the Duke’s dearest friend, long-term confidant and personal physician, Dr. Arthur Logan, died in New York. Fearing that the news of Dr. Logan’s death would have a shattering effect on his father, the Duke’s son, Mercer Ellington, who was a member of the band’s trumpet section, kept the news to himself for a few days. But, according to David Bradbury, it was on 29th November that Mercer finally told his father of Dr. Logan’s death. Mercer recalled, “For the next two or three days he (his father) unashamedly went through moments of mental hysteria…It was the first real breakdown I ever saw him get into.” This account means that Ellington, already very ill, would have heard of Dr. Logan’s death the day before the Preston concerts.

The following year was desperately sad for Ellington’s numerous followers. Joe Benjamin died on 26th January, 1974, after a car crash. Paul Gonsalves died in London on 15th May. Some reports say he died of an overdose. News of Gonsalves’ death was kept from Ellington. On 24th May Ellington himself died. A bandleader for fifty years and a monumental contributor to the great music of the twentieth century, he gave his final performances in late March. Harry Carney, who had been with the Duke since 1927, said he had nothing more to live for after Ellington had gone. He died on 8th October, 1974.

At the end of the second concert at the Guild Hall on that Friday evening, we made our way back to Preston station. It was now well after eleven o’clock. The night was bitterly cold and foggy. The station was quiet and our train had long gone. Over seven hours in a waiting room lay ahead of us. I arrived home at about nine on the Saturday morning. I had seen the great man for the last time.

Peter Gardner

April, 2018

Acknowledgements

I am particularly grateful to Liza Rivia, Library Assistant at the Harris Library, Preston, Lancashire. I also wish to thank Steve Marshall from Marshall McGurk, Maryport, Cumbria and Dawkes’ woodwind specialist, Sam Gregory, who has helped me with this, my twentieth blog for Dawkes, and all the previous ones.

Endnotes

(1) LPs LPM -3906 (mono) and LSP-3906 (stereo) of ‘…and His Mother Called Him Bill’ were released in May 1968. The CD ‘ Duke Ellington…and His Mother Called Him Bill’, ND 86287, has all the original tracks plus some previously unreleased material amounting to 16 tracks in all. A 19 track version of ‘…and His Mother Called Him Bill’ appears in the 24 CD set mentioned below..

(2) The LP APL1 – 1023 ‘The Eastbourne Performance’ was originally issued in November 1974. It has 11 tracks. A 12 track version of ‘The Eastbourne Performance’ appears in the 24 CD Set ‘The Duke Ellington Centennial Edition’ The Complete RCA/Victor Recordings (1927-1973).

Some Sources Used

David Bradbury, Duke Ellington (Haus Publishing, London,2005).

Duke Ellington, Music Is My Mistress: An Autobiography (W. H. Allen, London, 1974).

Mercer Ellington with Stanley Dance, Duke Ellington in Person (Hutchinson, London, 1978).

Richard Palmer, notes for ‘…and His Mother Called Him Bill’, ND 86287.

Programme for Duke Ellington’s British Tour, November 1973.

Patricia Willard, ‘The Last Recordings’ in booklet for ‘The Duke Ellington Centennial Edition’ The Complete RCA/Victor Recordings (1927-1973), pp. 109-116.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.